4.5 Dictionaries

4.5 Dictionaries

1. What Is a Dictionary?

A dictionary is a book where, if you have a word, you can look for its definition. But you probably weren’t wondering about a dictionary in the real world, you were probably wondering about a dictionary in computing. So, replace “book” with “data structure,” “word” with “key,” and “definition” with “value,” and you have the definition of a dictionary in terms of computing: a dictionary is a data structure where, if you have a key, you can look for its value.

Dictionaries vs. Variables

Values are the same here as they have been everywhere else: a value is an actual data value, like “Hello, world” or 5 or 5.1. What is a key, then? A key is the name that brings up that value. Now you might be thinking: wait, isn’t that just a variable? A variable is a name that, when referenced, brings up a value. And you’d be exactly right. Just as there is a 1:1 connection between variables and values, so also there is a 1:1 connection between keys in a dictionary and values.

So what makes them different? A dictionary is like a compilation of multiple key-value pairs that you can pass around together. Recall that one challenge of functions is that you can generally only return one value. A dictionary would let us return multiple values from a function. We’ve been able to do that before with lists, tuples, arrays, or some other structure like that, but a dictionary would preserve the ability to give names to those values by way of keys. So, in one way, we can think of a dictionary as a holding structure for several variables and their values.

Dictionaries vs. Lists

Like lists, dictionaries can hold multiple values. Depending on the language, these values might have an order to them. They might be sortable, or they might arrive in random order whenever they’re accessed. Either way though, both lists and dictionaries store multiple values.

The key distinguishing factor of a list, however, was that the values of a list had to be accessed via a numeric identifier called an index. A list would have a first value, a seventh value, and a twelfth value. The only way to access the seventh value was to ask the list for the seventh value.

Imagine, though, that each item in the list was a student, with their name and their current average; maybe this was stored as a tuple, a list, an array, or even a custom object like what we’ll discuss next unit. Now imagine that you knew you wanted to access David’s grades. How would you do that with a list? You would have to iterate over the list one item at a time looking for David.

Dictionaries use keys instead of numeric indices. What that means is that you access the values of the dictionary by putting in the key, not by putting in an index. If you want David’s grades, you use “David” as the key, and the grades pop right out. Keys are like non-numeric indices, but because they’re non-numeric, they can take on intuitive meanings, similar to variable names.

Imagine, for example, storing calendar items. The key for each list of calendar items could be the date itself, so if we wanted the calendar items for September 12th, we could use September 12th as the key instead of trying to calculate what numeric index corresponded to September 12th.

Question

How do you access values in a dictionary compared to a list?

Answer the question

Answer the question above the continue reading. iTELL evaluation is based on AI and may not always be accurate.

Dictionary Terminology

I keep referring to this data structure as a dictionary because the original language of this material refers to it as a dictionary, but different languages have different names for structures like these. They can sometimes have subtle differences, but generally the concept is the same:

- “Dictionary,” our current term, is so named because it echoes the idea of looking up words (keys) to find their definitions (values). Dictionaries suggest (but do not require) that the keys will be strings. Python, Swift, and the .NET languages use this term.

- “Map” is essentially a synonym to Dictionary. Some languages use the term “Map” because it echoes the mapping between keys and values and reinforce that keys need not be strings. Java and C++ use “Map”.

- “Associative Array” is another synonym. This term echoes the idea of two arrays with associations between them. PHP, JavaScript, and others sometimes use this term.

- “Hash,” “Hashtable,” and “HashMap” are implementations of Dictionaries or Maps. These terms are somewhat synonymous, although they contain an extra layer of detail; the term “Hash” refers to the way in which the data structure is constructed, not just how it is used. Perl, Lisp, and Ruby use some of these terms.

So, if you see any of these terms, know that they refer to effectively the same thing: a data structure comprised of a collection of keys mapped to values.

2. Dictionaries in Python

One of the things that makes Python unique as a programming language is the accessibility of its dictionaries. In most languages, dictionaries are a little clunky to use; they can only be declared with special constructors (we’ll talk about that next unit), and they’re only usable through methods. Python, however, gives us an in-line method for defining dictionaries.

Creating and Accessing Dictionaries

For example, let’s imagine we’re creating an inventory program. In this case, our keys would be product names, and our values would be the current stock of that item. How would we declare a dictionary with product names as keys and inventories as values? Well, we used brackets for lists and parentheses for tuples, I bet you can guess what we’ll use for dictionaries.

Figure 4.5.1

To define a dictionary, we enclose it in braces, as shown on line 2 in Figure 4.5.1. There are actually several other ways to declare them, too, but we really only need one, and this one is most intuitive in my opinion.

For dictionaries, we need to declare both the key and the value. In lists and tuples, we could jump straight to the values because the indices were inferred: the first item was 0, the second was 1, and so on. With dictionaries, however, our keys have to be supplied manually. So, each key-value pair in our dictionary is defined with the syntax key:value, as shown in line 2. Here, the key “sprockets” has the value 5, the key “widgets” has the value 11, and so on.

Functionally, this is the equivalent of creating four variables (sprockets, widgets, cogs, and gizmos), and assigning each the corresponding value (5, 11, 3, 15, respectively). However, because they’re contained within the dictionary, we can pass this list to a function or method, and it would retain access to every key and its associated value. Notice also that the order of the pairs is different when we print the dictionary on line 3 from the way we declared it: dictionaries in Python aren’t guaranteed to preserve the order of their values the way tuples, lists, and strings do.

Keys in dictionaries must be immutable: strings, integers, and floats can be keys. Tuples can also be keys, if and only if each individual item in the tuple is itself immutable (such as strings, integers, floats, or other immutable tuples). The reason for this is that if the key changes, the dictionary won’t know what value is associated with it; so it must guarantee the keys cannot change.

Values, on the other hand, can change. In fact, if this program was to be used for inventory management, we would absolutely need to change the values. We can do this by accessing individual items from the dictionary, as shown in Figure 4.5.2.

Figure 4.5.2

The print() statements on lines 3 and 5 show that the operation on line 4 does change the value associated with the key “sprockets” in myDictionary. This also shows how we access individual items from a dictionary: using the same syntax as with lists, strings, and tuples, but with keys inside the brackets instead of indices.

Adding to and Removing from a Dictionary

So, we’ve created a dictionary in Figure 4.5.2. How do we add new items to it? You might be tempted to try to call an append() method like we used with lists, but in dictionaries, we don’t need to. We create new key:value pairs in dictionaries the same way we create new variables: by assigning a value to a new key. Figure 4.5.3 shows this in action.

Figure 4.5.3

If we wanted to create a variable called gadgets and assign it the value 1, we would just say gadgets = 1. Similarly, if we want to create a new key in myDictionary called “gadgets” and assign it the value 1, we would just say myDictionary["gadgets"] = 1, as shown on line 7 of Figure 4.5.3. This creates the new key if it doesn’t already exist, or reassigns it if it does already exist, just as if it was a variable. Similarly, we can delete a key by using that special del operator, as shown on line 9. The print() statements on lines 4, 8, and 10 confirm that the key “gadgets” was added, then removed.

The reason we create and use keys this way is that a dictionary cannot have multiple copies of the same key; if it did, it wouldn’t know which value to return for that key. In other languages, the method for adding new keys is differentiated from the method for assigning values to existing keys, and those languages would throw an error if we tried to add a previously existing key again. Here, though, we have no way of adding a key besides assigning it as if it already exists.

Sometimes, though, we might want to check to see if a key exists before assigning it. For example, imagine if we were building a phonebook app, and if the user tries to create a key that already exists, we want to prompt them for a different key instead of changing the phone number of the existing key. We can do that by checking if a key exists before referring to it, as shown in Figure 4.5.4.

Figure 4.5.4

The in operator, by default, operates on the keys of the dictionary. In Figure 4.5.4, “David” is already a key in the dictionary, so line 8 returns True, causing the code to try again with “David2” as the key. We can also use the keyword in to avoid the error caused when we look up a key that isn’t in the dictionary, as shown in Figure 4.5.5.

If we’re uncertain if a key will appear in the dictionary, we should either (a) check if it appears using in before trying to access it, or (b) be prepared to catch the KeyError shown in Figure 4.5.5.

Figure 4.5.5

Question

How do we add new items to a dictionary in Python?

Answer the question

Answer the question above the continue reading. iTELL evaluation is based on AI and may not always be accurate.

Traversing Dictionaries

As noted, the main benefit of dictionaries is that they give us useful keys so we can jump straight to the value we want. However, there will still be lots of times we want to traverse every item in a dictionary. For example, in our inventory program, perhaps we want to make sure to order more of any item that drops below 5. There are a number of ways we could do this. First, if we don’t care what key gives us these values, we could iterate over the values() directly, as shown in lines 5 through 7 of Figure 4.5.6.

Figure 4.5.6

More commonly, though, we’ll want the key and the value. So, instead, we could iterate over the keys, and then grab the value from the dictionary based on the key, as shown in lines 5 through 8 of Figure 4.5.7. Notice that here we’re iterating over myDictionary.keys() in line 5, but this has the same effect as iterating over myDictionary itself; it assumes it should use keys if we don’t tell it otherwise.

Figure 4.5.7

It’s also possible, however, to iterate over the keys and values simultaneously. This is a shortcut similar to the for-each loop itself where multiple parts of the sequence can be loaded into variables. Here, it’s assumed that the order is key, value, as shown in line 5 of Figure 4.5.8. So, we can iterate over the keys in the dictionary, the values in the dictionary, and the keys and values together.

Figure 4.5.8

Question

What is a benefit of dictionaries for traversing every item in a dictionary?

Answer the question

Answer the question above the continue reading. iTELL evaluation is based on AI and may not always be accurate.

3. Dictionary Applications

Dictionaries are extremely powerful data structures, even when just used the way we’ve discussed them so far. However, some of the benefits of dictionaries are that they allow us to create a low-overhead version of object-oriented programming. Object-oriented programming is our next chapter, and it’s a big and important topic, so we’ll preview it here.

Simple Dictionary Applications

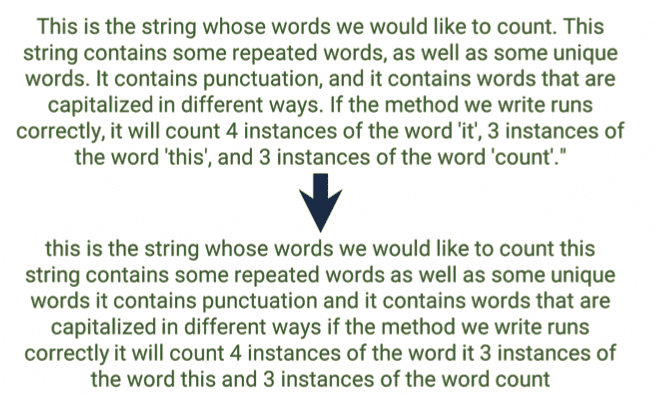

With a single dictionary, there are a lot of things you can do. For example, imagine you want to count the most common words in a book. If you have the book in plaintext, how would you do that? First, you’d likely replace all the punctuation marks and other symbols with spaces, so that you don’t get stuck treating a word with a period after it as a different word from its other appearances. Then, you’d probably change the entire thing to lower or upper case so you don’t have to worry about capitals.

FIgure 4.5.9

Figure 4.5.10

After that, though, what would you do? You very likely might split the book by spaces, then start iterating over each individual word. When you find a word you haven’t seen before, you add it as a key to your dictionary with a value of 1. When you find a word you have seen before, you look for it in the dictionary and increment its value. In the end, your keys are all the words in the book, and your values are all the counts of each word.

Alternatively, imagine you were creating a seating chart for a wedding. How would you do this? You could have a list of all the seats, or a list of tables each with a list of seats. However, this would mean you would need to know the table and seat number to look who was sitting there. In all likelihood, that’s backwards: you’re probably not looking for, “Who’s at table 5 seat 3?”, you’re looking for, “Where is Addison sitting?” So, you could do this with a dictionary instead: the keys are the individuals’ names, and the values are the seat assignments, as either strings (e.g. “5-3”) or as tuples (5, 3). That gets into our more complex application of dictionaries: merging dictionaries with lists, tuples, arrays, or other dictionaries.

Figure 4.5.11

Dictionaries and Lists

A big part of the usefulness of dictionaries comes when we use them in conjunction with other lists or dictionaries. For example, imagine we’re keeping track of students across a school at a given time of day. We might have a dictionary of classrooms, where the keys are the classroom numbers and the values are lists of students in these classrooms. That way, at any given time we can look for how many students are in a class as well as which students are in a class.

Alternatively, imagine we’re building a more comprehensive address book program. We want each person in the address book to have a name, an address, a phone number, and an email address. We want to access them by their names. So, the keys would be the names, and the values could be a tuple or list, containing their address, phone number, and email address.

However, that design still poses a problem: because the address, phone number, and email address are stored in a list or tuple, we have to remember which index corresponds to which kind of data. If we forget, we may load the phone number as the email address or vice versa. However, dictionaries let us use non-numeric keys instead of numeric indices, and that is immensely powerful.

Dictionaries as Simple Object-Oriented Programming

We’ll cover object-oriented programming in the next unit. For now, though, what you need to know is that an object is a custom data type that can contain multiple individual variables and methods, each with its own name. That’s powerful; we could, for example, create a Person object that would let us store a first name, last name, and phone number together in one data type, but each individually accessible.

However, dictionaries actually already let us do that. In this address book example, we had a dictionary of tuples or lists, where the three items on the list represented addresses, phone numbers, and email addresses. Instead of collecting these in a list, however, we could collect them in a dictionary, where the keys are the types of information (“address,” “phone number,” and “email address”), and the values are that individual person’s values.

The unique twist here is that in this case, we would have lots of dictionaries, each with only a few items. Most importantly, though, each dictionary would have the same keys. So, we could iterate over every person in the address book and get their email address just by requesting their email address by name from their individual dictionary. This is immensely powerful.

Question

Automatic question-generation has failed. Please try again.

Answer the question

Answer the question above the continue reading. iTELL evaluation is based on AI and may not always be accurate.

4. Dictionary Applications in Python

Before moving on to these super-advanced types of dictionaries, let’s explore some of the more accessible applications a little bit more.

Simple Examples of Dictionaries

First, let’s see some code that counts the words in a string using a dictionary. This is shown in Figure 4.5.12.

Figure 4.5.12

We start by defining the string, myString, on line 1. We then modify it on lines 3 through 7 it so that it contains only the words: we remove punctuation (lines 3, 4, and 5), make it lower case (line 6), then split it by spaces so that we have a list of words (line 7). We then iterate over that list of words starting on line 10. For each word that isn’t yet in the dictionary, the conditional on line 11 is False, so we add it to the dictionary with a value of 1 on line 14 because 1 instance has been found. For each word that is already in the dictionary, the conditional on line 11 is True, so we just increment its counter on line 12. In the end, our dictionary contains all the words in the string as keys, and the count of these words as their corresponding values.

Question

What is the purpose of the code snippet provided in Figure 4.5.12?

Answer the question

Answer the question above the continue reading. iTELL evaluation is based on AI and may not always be accurate.

Dictionaries and Lists

For our classroom roster, we first define a dictionary of classes, as shown in lines 1 through 5 of Figure 4.5.14. Each class has a name as the key and a list of students (as defined by the brackets) as the value. Notice here how easily we can use lists as values instead of just simpler values on their own; we just put the same brackets and declaration as we usually would to define a list.

Figure 4.5.14

Then, we look up all the students in Computing with classes["Computing"]. This returns a list of students, which we print on line 7. Then, we decide to add Francis to History. We get the list corresponding to History with classes["History"] on line 9, and because this is a list, we can call append("Francis") on it. Then, when we print the History class roster on line 10, we see Francis is included.

For our address book, we sub out the lists for tuples, as shown in Figure 4.5.15. Here, we see on line 5 that we can print David’s complete information by printing his tuple, or we can print Dana’s phone number alone on line 6 by knowing that the phone number is at index 1. But that last note is exactly where we find some real power in dictionaries: why should we have to remember that the phone number is at index 1 when we can instead use a dictionary and store the phone number with key “phone number”?

Figure 4.5.15

Dictionaries as Objects

One of the most powerful parts of using dictionaries is the ability to have multiple dictionaries with the same keys, but different values. This data structure is a low-overhead version of object-oriented programming, which we’ll cover in the next chapter. To start, let’s convert that address book code to use these nested dictionaries in Figure 4.5.16.

Figure 4.5.16

In this case, our code has gotten a bit longer: instead of the inferred numeric indices, we now supply actual keys for the dictionaries, as shown on lines 1 through 6. Compare Figure 4.5.16 to Figure 4.5.15 to see the difference. However, the trade-off is that this is now much easier to use. We don’t need to remember the order in which the different types of data are contained inside the items of the dictionary; we just need to remember that phone number is stored with key “phone”, address with key “address,” and email address with key “email”. Don’t underestimate that trade-off: it might seem easy to remember this for these three values, but imagine if you were dealing with several different dictionaries with several different types of data, or with one dictionary with twenty different fields. With lists, you would need to remember the index for each type of data, as well as remember to declare them in the right order. With dictionaries, you merely need to remember the name for each type of data, similar to how you would remember a variable.

Note that this merely implements something resembling object-oriented programming in the simplest terms. In real object-oriented programming, we can have methods as well as variables contained within each item, as well as other advanced features. Still, this approach gives a glimpse of the power of object-oriented programming, as well as a way to realize some of its benefits with relatively low overhead.

To show this off, let’s take one more example. Imagine we’re teaching a class with five students, and we gave a multiple choice test with five questions. Now, we want to grade the test. We could do that with dictionaries, as shown in Figure 4.5.17.

Figure 4.5.17

Here, we create three students and give them five answers to the five questions each on lines 4, 5, and 6. We also create an answer key on line 1. Then with the for loop on line 9, for each student in the dictionary of students, we grab their answer dictionary and store it in answers. Then, for each question in the dictionary answers, we grab its answer with the for loop on line 12. If the value for answer to the key question matches ANSWER_KEY’s value (answer) for the corresponding key (question) in the conditional on line 14, we add one to grade on line 15. Then, at the end on line 17, we create a new key-value pair between “grade” and their score, stored in the variable grade.

The loop at the end (lines 19 to 21) isn’t totally necessary here; we could have printed out the grades in the first for loop. However, it’s here to demonstrate the power of knowing that every element in the dictionary will have the same key. We know every student will have a “grade” key because we created it for each student on line 17, so we can run a loop over all students, getting their grade.

5. Dictionaries and Turtles

Over the past several lessons, our turtles code has gotten more and more complex. In some ways, that’s not bad: it’s a complicated program, and its goal is to show you how the simple rules you’ve been learning can be chained together to form massively complex programs.

In other ways, though, it’s a bad thing. Giant multi-layer if statements are often frowned upon because they’re difficult to read and navigate. We might also notice that our commands are, in some ways, like keys to a dictionary: it’s just that in this case, the values are the lines of code that run in response, not variables. Could we create dictionaries whose values are actually references to functions? Yes! Follow along in DictionariesandTurtles.py to see how.

Replacing Conditionals with Dictionaries

Let’s start by trying to replace the giant series of conditional statements that get the user’s input with something dictionary-based. Take a look at that conditional inside getCommandFromUser(): notice anything? Every branch follows the same pattern: get arguments, then create commandTuple with the command in the first spot. Instead of this complex branching series, we could instead create little func- tions for each, and then just call the function based on the command name as estab- lished by a map. Let’s try that out.

You might have to trust me for now when I say this code is better. It seems incredibly strange. What have we done? We’ve taken the entire body of getCommandFromUser() and executeCommand(), and we’ve split each branch into its own function, named things like getSnowflakeCommand() and executeTextCommand(). Why did we do that?

Take a look at COMMAND_DICTIONARY. Here, we see every command the user can enter, from turn to end. This is a dictionary, so the command names themselves are keys. What are the values? Other dictionaries! What are the keys of these other dictionaries? Every one of these dictionaries has the keys "get" and "execute" What are the values? Brace yourself: the values are the functions themselves. Functions are variables. So, we can put the function names here.

So what happens? Well, the while loop that drives the program is unchanged. So, let’s take a look at getCommandFromUser(). Previously, this would get a command from a user, then run a big conditional statement checking the command’s value. It would choose which arguments to get based on the command’s value. It was a long function. What about now? It’s only 6 lines! How did we replace over 30 lines with 6?

The first two lines are the same: we get a command from the user. However, instead of using that command in a conditional, we instead use it as the key to our COMMAND_DICTIONARY. If it’s not a key in the dictionary, our commandTuple is just the “Invalid” tuple. If it is a key in the dictionary, though, the magic happens.

Replacing Conditionals with Dictionaries II

Let’s take a close look at the line here: return COMMAND_DICTIONARY [command]["get"](). What a crazy line. It starts with return, so we know what comes out of the rest of it must be our commandTuple. We start from left to right. COMMAND_DICTIONARY[command] takes the command and uses it as the key to the dictionary. We know the command is valid because of the earlier conditional. So, what comes out of COMMAND_DICTIONARY?

Let’s assume the user’s inputted command was ‘forward’. So, our line is now COMMAND_DICTIONARY["forward"]["get"](). The result of COMMAND_ DICTIONARY["forward"] is another dictionary. This other dictionary has two keys, “get” and “execute”. So, COMMAND_DICTIONARY[“forward”][“get”] returns the value associated with “get” in the second dictionary. What value is that? getForwardCommand. It’s the name of the function. Then, the end of the line is (), which tells Python to actually run the function.

So, COMMAND_DICTIONARY[command]["get"]() tells Python to run the “get” function associated with the command the user entered. That function does the same thing it did before: it gets the user’s input (in this case, just a distance), creates the commandTuple that holds the command and the arguments, and returns it. Since we’re returning the result of COMMAND_DICTIONARY[command] ["get"]() as well, we return the commandTuple all the way back out to the main program.

After all that work, the result is exactly the same. We could have made these changes and our users would never even notice. Notice that executeCommand() is the same. Instead of a big conditional, it uses a map to find the right execute command to run. Here, though, it actually passes the commandTuple itself so that the execute commands can have their arguments. Other than that, the only difference is that we have to define recording, recordList, and allCommandsList as global within the execute functions for record, stop, and save.

As I’ve said repeatedly before, don’t worry if this is confusing. In fact, if this isn’t confusing, please contact me so that I can hire you to teach this class. This is an incredibly complex example of Python reasoning and syntax. It’s taken me several hours to compile this to this point, and I’ve learned a lot in the process. The goal is not for you to understand exactly how this works. The goal is for you to see an example of a complex, authentic Python program as it is developed. Do try to understand it as best as you can, but don’t be discouraged by it.

Why Is This better?

The big question you might have is: In what way is this actually better? “I understood the earlier way!” you might say. “You’re just making it more complex on purpose to show off these principles!”

While that’s partially true, this actually is better. Why is it better? Good programming practice is typically built around lots of small, reusable functions. Originally, our main program was extremely large. When we converted getCommandFromUser() and executeCommand() to functions, we shrunk down the size of the main program, but we replaced it with two even bigger functions.

Now look at our code, though. No function over 8 lines. Our main program code is only 7 lines, 11 if you include the initializations of things like command and recording. Our functions are highly reusable: we could copy executeDrawSnowflake() to any program that stored arguments the same way we do.

Consider also how we would add new commands to this now. We would add them to the COMMAND_DICTIONARY, then also create dedicated functions for them. However, we don’t have to trace through the program code to find the right place to add the functions or their reasoning. We don’t have to create a new branch of a giant conditional. Just by adding them to the dictionary and creating their functions, we add them to the program. We could copy and paste someone else’s functions directly into our code without worrying about integrating it beyond just adding it to our list of supported commands.

That’s what makes this code better: small, modular functions with very few interdependencies.

Last updated at